We’ll have to rewrite the textbooks… again. Some parts of the body – including the tissues of the brain and testes – have long been considered to be completely hidden from our immune system. Last year scientists made the amazing discovery that a set of previously unseen channels connected the brain to our immune system; now, it appears we might also need to rethink the immune system’s relationship with the testes, potentially explaining why some men are infertile and how some cancer vaccines fail to provide immunity.

Researchers from University of Virginia School of Medicine discovered a ‘very small door’ which allows the testes to expose some of its antigens to the immune system without letting it inside. For the past four decades the testes have been regarded as having ‘immune privilege’, meaning they don’t mount an immune response when introduced to materials the immune system considers foreign. Together with the brain, eyes, and placenta, inflammation in these parts of the body would be seriously bad news, which could explain why they are all physically or chemically hidden from the white cells and antibodies which protect us from infection.

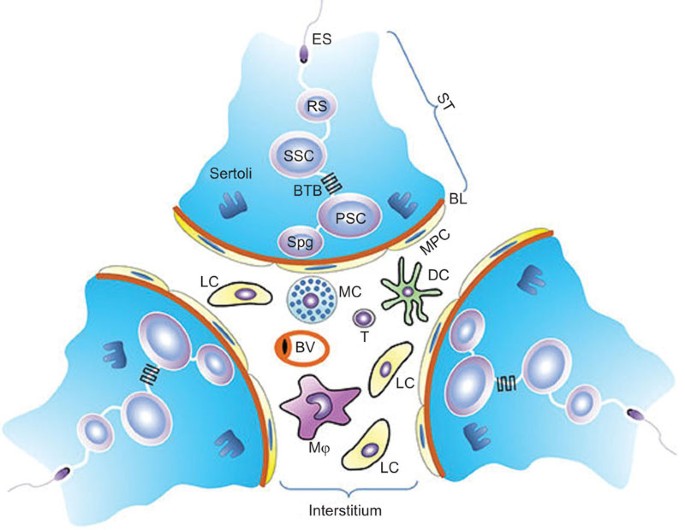

This ‘immunity from immunity’ means any sperm outside of the testes can produce an autoimmune reaction, proving that the body considers its own sperm as foreign. At least that’s the current thinking, which might need to be modified if this new research is verified. Separating the sperm-producing tissues in the testes from the blood vessels is a layer of tissue called Sertoli cells, serving as a kind of nurse cell to the developing sperm. Sertoli cells lock together in such a way that they effectively form what’s called a ‘blood-testes barrier’, preventing T-cells in the blood from sniffing out the growing sperm.

The system works well, but isn’t foolproof – in up to 12 percent of men with spontaneous infertility, the immune system recognises a chemical on the surface of sperm cells called the meiotic germ cell antigen (MGCA), suggesting they’ve met previously and don’t tolerate it as native to the body. The immunologists hypothesised this particular autoimmune response might say more about a break-down in tolerance than a break in the blood-testes barrier, suggesting that there were reasons to suspect MGCA wasn’t as hidden as previously thought.

By focussing on two types of MGCA in normal and genetically altered mice and analysing the mouse’s T-cell tolerance to the antigens, the researchers found the Sertoli cells can ‘leak’ some types of the antigen into the blood vessels. “In essence, we believe the testes antigens can be divided into those which are sequestered [behind the barrier] and those that are not,” said researcher Kenneth Tung. Not only could this discovery provide insight into how infertility can arise in some men, it could also help immunologists understand how cancer cells sequester, or hide, their own antigens, explaining why certain cancer vaccines can fail.

“Antigens which are not sequestered would not be very good cancer vaccine candidates,” said Tung. So far the research has only been done on mice and is yet to be confirmed in humans, but it lays the groundwork for exciting new research into the subtle interactions across a wall which was previously considered to be impermeable to the immune system. Just last year a team of researchers from the same university uncovered a network of channels in the nervous system of mice and humans that crossed a similar barrier between the blood and the brain, prompting excitement at having the ‘rewrite the textbooks’. Once again, it might seem the guides on immunology might need a new edition.

This research was published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.